How does the Christmas story end?

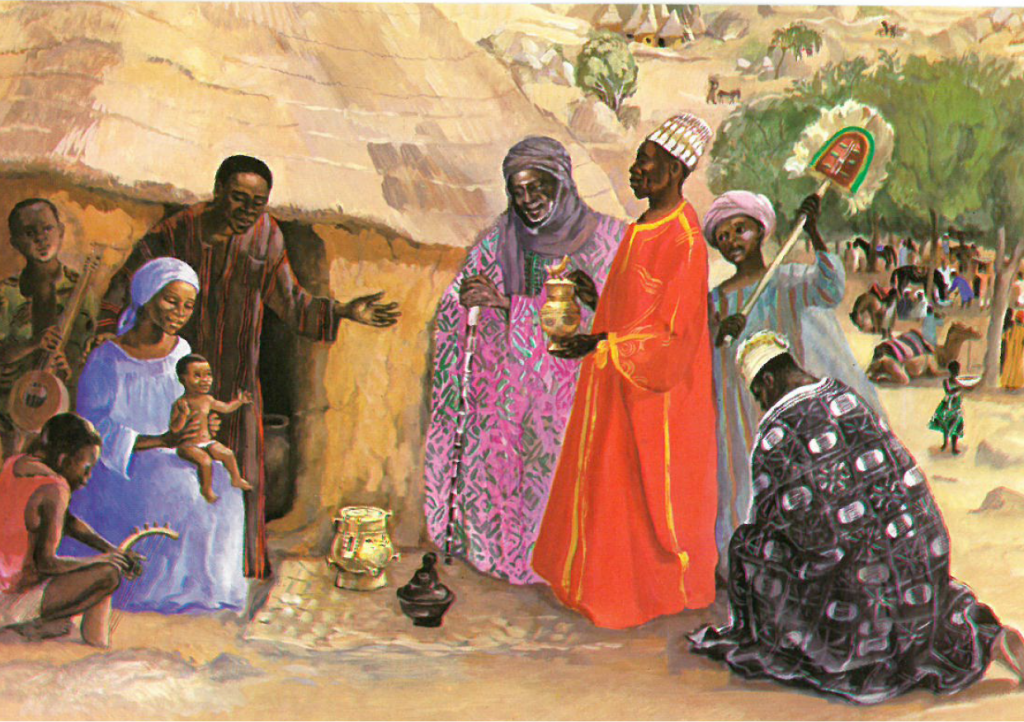

We certainly know how it begins. Picture the image of Jesus in the manger and quickly the biblical story swells up within us. Gabriel’s annunciation to Mary, the sharing of the news with cousin Elizabeth, Joseph’s shock, a midnight dream, returning to Bethlehem, the choir of angels, the shepherds filled with fear and finally…the climax of Jesus birth. He is born in a stable because there is no room in the inn.  The shepherds visit him. And the wise men. And we are moved to immeasurable, undeniable compassion and thanksgiving for the “good news of great joy.” Jesus Christ has come to redeem the world, part of God’s grand narrative for a salvific plan. Many of us can recite the verses by heart and recount every step of the biblical depiction. At our Christmas services, we are full of awe and wonder for what God has done through this little child born for us. We sing “Joy to the World” embracing the tender Christmas moments with our family. The Christmas story ends with those who came to visit him and give witness to his birth. He is Lord!

The shepherds visit him. And the wise men. And we are moved to immeasurable, undeniable compassion and thanksgiving for the “good news of great joy.” Jesus Christ has come to redeem the world, part of God’s grand narrative for a salvific plan. Many of us can recite the verses by heart and recount every step of the biblical depiction. At our Christmas services, we are full of awe and wonder for what God has done through this little child born for us. We sing “Joy to the World” embracing the tender Christmas moments with our family. The Christmas story ends with those who came to visit him and give witness to his birth. He is Lord!

But how do our brothers and sisters in Congo retell the Christmas story?

During my recent trip to Congo, I was confronted with a profoundly different ending and tone to the Christmas story. The Congolese do not stop with the adoratio, for the very next verses in Matthew depict of the killing of the innocents. Jesus’ birth is not good news for Herod who seeks to find and kill Jesus by commanding that all male children under 2 years age will be killed. The Congolese depiction goes on to include this passage and how Jesus fled. I learned that many of the Congolese Christmas pageants include children lined up in the front pew of the church and a depiction of their being killed.

During my recent trip to Congo, I was confronted with a profoundly different ending and tone to the Christmas story. The Congolese do not stop with the adoratio, for the very next verses in Matthew depict of the killing of the innocents. Jesus’ birth is not good news for Herod who seeks to find and kill Jesus by commanding that all male children under 2 years age will be killed. The Congolese depiction goes on to include this passage and how Jesus fled. I learned that many of the Congolese Christmas pageants include children lined up in the front pew of the church and a depiction of their being killed.

How does this profoundly enlarged narrative and tone of this story reflect the differences in our respective cultures? Why do we stop at Matt 2:15? Why do we not continue with the very next passage separated only by a numbered verse? In the west, the overall theme of Jesus’ coming is one of joy, assurance and of God’s goodness. We note his Coming occurs in the midst of Roman oppression and in the squalor of a stable, a reminder of how Jesus meets us in all circumstances and stations of life but we end with the hope Jesus brings through the very miracle of his birth celebrated by all who adore and worship him at the manager. We seek hope and joy in our “silent night, holy night, all is calm, all is bright” Christmas message. For the Congolese, I am told, the inclusion of the killing of innocent children reflects years of civil war, the tragic impact of violence and strife, and the modern day realities akin to the Christmas story of 2,000 years ago. A more holistic depiction, including the fleeing to Egypt and Jesus’ return to begin his adult ministry, are assurance of His presence and a reminder that these biblical violent acts are also experienced in the tragedy of civil strife. Even today, Congo is not free to live in assurance that another war will not erupt where many innocent lives will be lost.

At this time of year when we remember what God gives us in the gift of God’s Son, let us also remember how our Congolese brothers and sisters have suffered in ways which are unthinkable to most of us. We can be thankful for the way the Congolese culture illuminates another Christmas passage that we are inclined to skip. And we can be reminded that whatever life circumstances we bring to God’s Word, Congolese or Westerner, God meets each of us with a meaningful biblical passage. Let us give thanks for this opportunity to see a broader depiction of the Christmas story through Congolese eyes this Christmas.

“And we know that in all things God works for the good of those who love Him, who have been called according to His purpose.” Romans 8:28