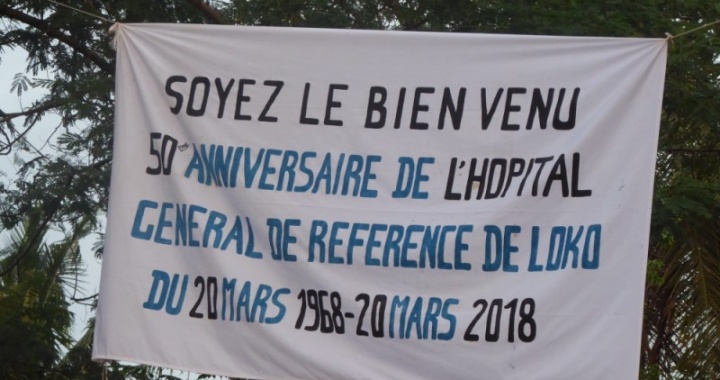

Partners on the Journey: A Special 50th Anniversary Blog Series, Part 4 By Mike Hertenstein

Partners on the Journey: A Special 50th Anniversary Blog Series, Part 4 By Mike Hertenstein

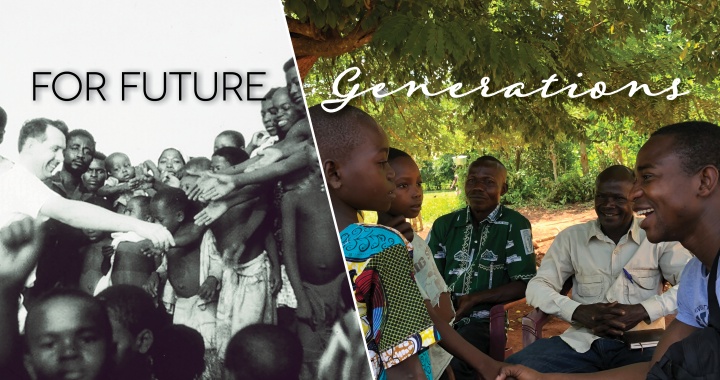

Over the next two years, Paul and Lois Carlson and their two young children followed a path of preparation for a long-term commitment to the mission field. Paul trained in tropical medicine, the family took language lessons in France, before arriving in the Congo in July of 1963.

In Wasolo (that remote area known as “the Forgotten Corner”) was an 80-bed hospital and, just outside of town, a leper colony. The work would be non-stop, under unimaginably difficult conditions. Paul would be summoned, sometimes in the middle of the night, for emergency cases, often operating by lantern-light.

“Monganga Paul” is what the people called him, “my Doctor Paul” – for his patients felt close to this warm and ever-available doctor, despite a patient-doctor ratio of 100,000 to 1. Carlson seemed to thrive in it, making the best of things despite a lack of resources and crazy workload.

If he wasn’t wakened in the night, he might be wakened in the morning by goats in the yard or birds in the jungle. After motorbiking down the hill to the hospital, Dr. Paul would make his morning rounds of the 50-bed facility and overflow building with a Congolese nurse, monitoring cases from malnutrition, meningitis, kids with whooping cough, mothers in labor. Medicine was practiced, lives were saved, but lost, too, under impossible conditions that would make a MASH unit seem like a posh research hospital. But there was nobody else, and relatively nothing else in the way of many ordinary resources. Paul hated charging even 5-10¢ for prescriptions or two-bucks for emergency surgery – but it was the only way to get money to buy more medicines.

Meanwhile, Lois Carlson, with other duties kept busy homeschooling their daughter (their son was at boarding school) and teaching village girls homemaking skills – when she wasn’t leading a crew to the spring to fill 50 gallon barrels for the mission – and hospital – water supply.

Missionary nurse, Jody LeVahn, preceded the Carlson’s at Wasolo and welcomed their arrival. She quickly became like another member of their family, present to help with everything from anesthesiology to translation.

The missionary vocation generally requires “a passion for the impossible,” and the Wasolo station offered many impossibilities before which the Carlsons found it impossible to say no.