Dr. Paul Carlson

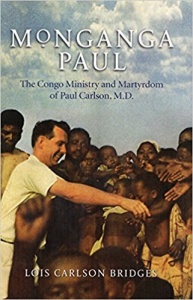

In 1964, Dr. Paul Carlson, a medical missionary with the Evangelical Covenant Church, was killed while serving in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Shortly after, Paul Carlson Partnership was created in his honor to continue his work in partnership with the Covenant Church of Congo.

Who was Paul Carlson?

By Joan O’Connell Hamilton

Stanford magazine, September 1991

Published by Stanford Alumni Association, Stanford University

Reprinted with permission

Inside Stanleyville’s Victoria Hotel were 250 hostages, most of them Belgians unlucky enough to be in the region when the rebels, known as Simbas, staged their assault. There were many families with children, a smattering of Americans, several diplomats. But one prisoner, a kind, 36-year-old physician and missionary, would later be remembered more than the others. He moved among the prisoners, setting up his own tiny clinic to treat the sick and injured, making jokes to calm their nerves. “I have never seen a man behave like that,” a fellow prisoner, a Belgian engineer, would later write, calling Carlson “the one real man I have ever met in my life.”

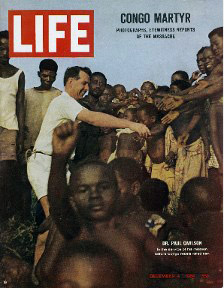

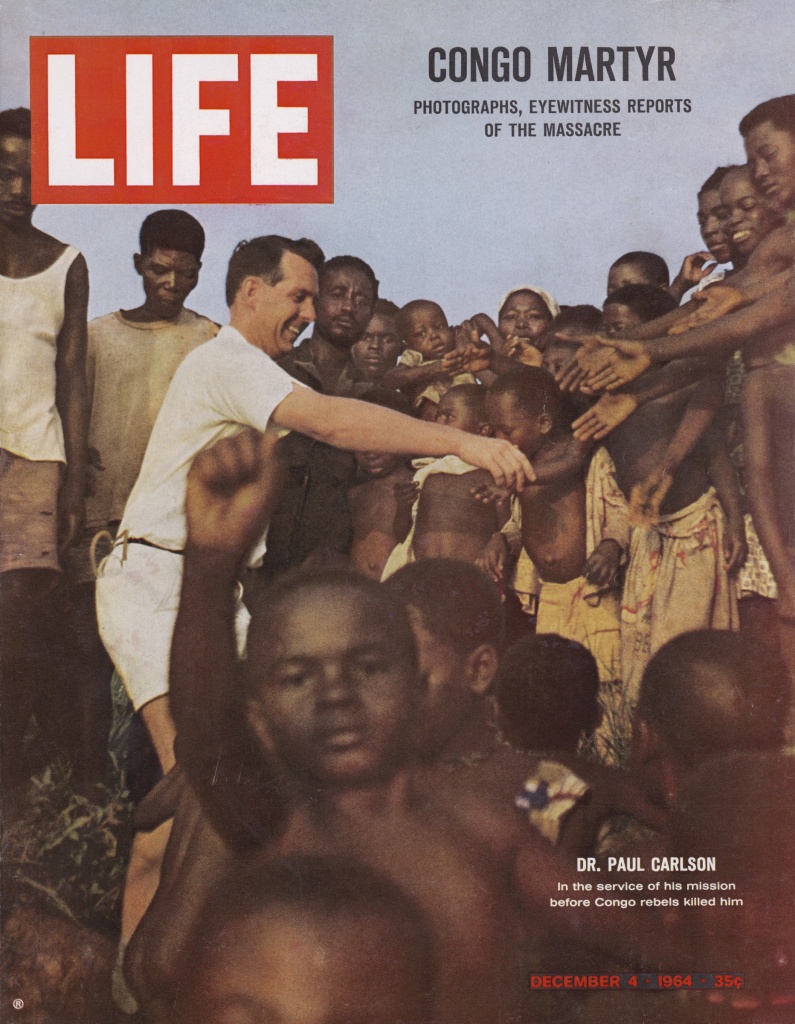

Between ads for Ford Mustangs and Coca-Cola, Life magazine ran a spread on the Congo during the first week of December 1964. It was no exotic travelogue: Africa was erupting and the Congo was its flashpoint. The Congo had been given independence suddenly and unexpectedly from Belgium in 1960 and was highly volatile. For five months, rebel insurgents had held the city of Stanleyville, deep in the country’s interior, and had proclaimed a “People’s Republic.”

From childhood, Paul Carlson had a calling to help others. The son of Swedish immigrant Gustav Carlson, a Southern California machinist, Paul earned a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from Stanford in 1951, and finished medical school at George Washington University five years later. Despite the fact that he had a wife and two children, in 1961 Carlson responded to an urgent appeal by the Christian Medical and Dental Society for doctors in the Congo. Instead of settling down to a potentially lucrative private practice in Redondo Beach, Calif., he took a six-month missionary tour in Africa. Although the young doctor was deeply touched by the experience, he returned to Southern California and set up his practice. But the vast medical needs of the people of the Congo continued to haunt him. Finally, he told a friend, “I’m going back. I can’t stand doing hernias and hemorrhoids any more.”

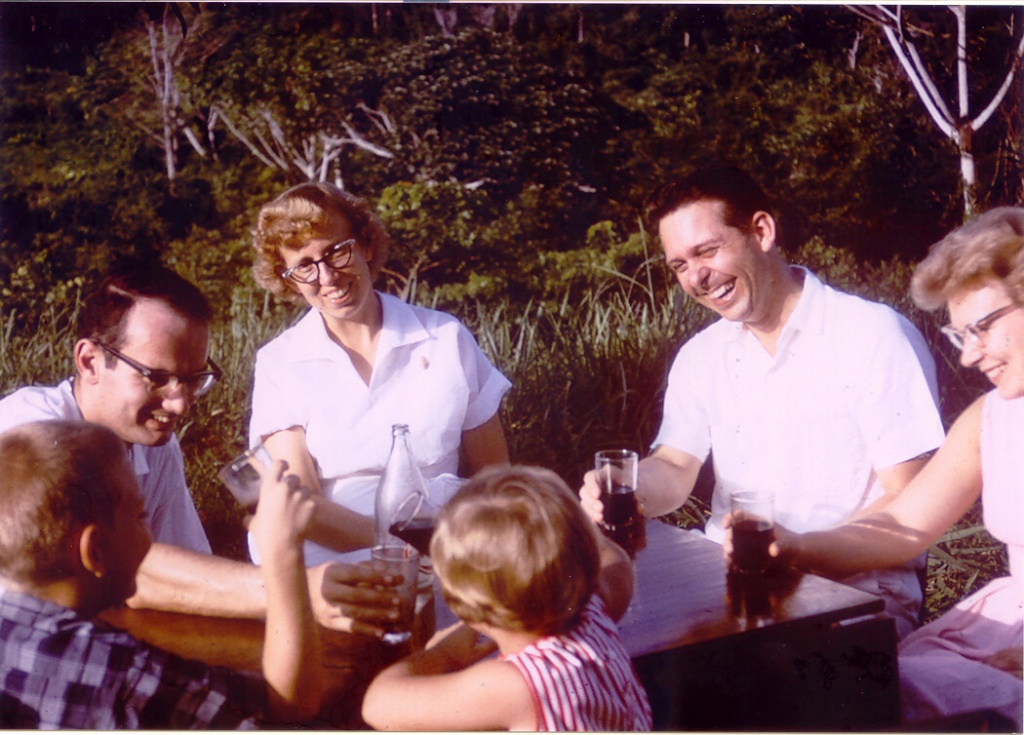

Carlson and his family left for the Congo in 1963, trading his then-comfortable $12,000-a-year income in California for roughly $3,000 in missionary pay and a backyard full of crocodiles. The Carlsons moved to Wasolo, a simple clearing in the jungle that locals called “The End of the World.”

Their new environs included a leper colony and an 80-bed hospital serving 100,000 people. The family was only a few yards from impenetrable rain forest, but half a mile from fresh water. “I didn’t want to go,” recalls Wayne Carlson, 36, now a Chicago physician. Back then, he was a 9-year-old boy who missed his American friends and wasn’t sure he was ready for a home where “bugs and snakes fell from the grass roof.”

For almost a year, Carlson fought the daily struggles of the missionary. He was devoted to his patients, concerned about his family, and anxious to spread the word of the plight of the poor people of this equatorial region. He spent 95 percent of his time trying to heal—which at times meant fixing plumbing or repairing a car on a “house call” in a nearby village. Fun consisted of family Scrabble games, hymn singing, and the children’s adventures in raising animals. It was a hard life, but Carlson felt fulfilled. The natives took to calling him Monganga Paulo, or “My Doctor Paul.”

Unfortunately, Carlson picked a bad time to do good work. In the early fall of 1964, the political situation in the region was deteriorating. Carlson became sufficiently concerned that he moved his wife, Lois, and their two children across the Ubangi River to the Central African Republic. He, however, returned to his post, hoping to stay as long as possible to minister to his patients.

Carlson was betting that the rebels would not bother doctors, but he had contingency plans to join his family if the situation became more violent. “He worried that if he left, the rebels would come in and kill all the patients,” remembers Wayne.

Sadly, he bet wrong. In September, Dr. Paul was arrested, then tortured physically and mentally. He was sent 300 miles south to Stanleyville where he became a pawn of the Simba rebels. They repeatedly sentenced him to death as an American spy, sparing him whenever they thought they were about to win concessions from the Belgian and American governments, which opposed their activities. Carlson’s worried family spent their days listening to shortwave radio, praying for word of his safety.

As morning dawned in Stanleyville on November 24, 1964, however, the American and Belgian governments decreed there would be no more concessions. The savage rhetoric from the rebel leadership prompted the Americans and Belgians to launch a rescue mission. U.S. airplanes droned overhead as Belgian paratroopers dropped down on the outskirts of town. The rebels were anxious and full of adrenaline. And then Carlson’s final ordeal began.

The brutal Simbas routinely killed and tortured their enemies, sometimes consuming the dead prisoners’ organs in front of others. With the paratroopers approaching that morning, the rebels assembled the Stanleyville prisoners in the street. They put women and children in the front rows. Crazed with fear and anger, the Simbas began chanting “kill” in Swahili.

What followed was a nightmare. A Simba guard opened fire on a woman, emptying his rifle into her bleeding body. Other soldiers fired blindly into the crowd, targeting parents who had flung their bodies over children. Some prisoners feigned death. Carlson and others at the rear of the group ran toward a wall, hoping to leap to safety. But before trying to scale the wall, Carlson urged another prisoner, a missionary as well, to go first. As Carlson climbed, he was sprayed with machine gun fire and fell to the ground. Belgian paratroopers arrived at the scene shortly after Carlson was killed, and the rebels fled.

A photo of the young, clean-cut missionary with unseeing eyes, an ID tag looped around his neck, soon was seen around the world. It was taken only minutes after his death, as he lay in a field of casualties. In the following weeks, Carlson’s photograph was featured on the cover of Time magazine, and his story would become a riveting tale of martyrdom from the turbulent Congo.

Life managing editor George P. Hunt called Carlson “a heroic man of God who lived for the African—only to be killed by his hand.” It’s unlikely, though, that Carlson would have penned such an epitaph. “The secular perspective was that this was a horrible tragedy,” says Carlson’s brother, Dwight, a Torrance, Calif., psychiatrist. “There was not an understanding of why someone would give his life. Paul had a strong religious faith. He had a calling, he went, he was faithful to his calling. I think he would have said that human beings took his life and that was unfortunate, but there was a higher benefit.”

In the last tape Carlson dictated and sent home before his arrest, Dr. Paul clearly had no simplistic view of his mission.

“The people are trying to take over more and more, yet realize their own inability to handle so many of these things,” he told his father, who is still alive at age 92. “There are times when they know of repression, when they know of opposition, when they know of problems faced by other Christians in the country. You see, it’s a tremendous burden.”

Today, a medical foundation formed in Carlson’s name supports the Central African hospital where he worked. It sponsors such activities as agricultural projects and a fish farm in the Wasolo region. His son, Wayne Carlson, hopes to retire early from his private practice and return to the Congo to continue his father’s work. “Like a lot of us who go through medical school and residencies and internships, my father had lost perspective on what medicine is about,” says Wayne. “But he found it again. It’s about helping people.”

Paul Carlson’s friends and family still speak lovingly of an apolitical man who sought no fame or fortune. Carlson was heroic, not because of his martyr’s death, but because he was committed, against all odds, to healing others. In the New Testament he carried with him, Carlson had written the date and a single word the day before he died. The word? Peace.

More Resources